by Jim Goodnight

The warmth of his personality and the wit, wisdom, and energy of his conversation have caused us to seek the company of this man. We respect his knowledge and sense his genuine interest in ourselves and in our learning. His presence imposes on us a desire to please and compels us to try harder. Our encounters have not been superficial; he has given of himself generously. In teaching us neurology, he has touch us much.

We acknowledge our appreciation.

James E. Goodnight, Jr. ‘68

Taken from Aesculapian, Baylor College of Medicine Yearbook, 1968.

In medical school, when I was first being groomed and charged with caring for my fellow man, one particular set of encounters stands out as profoundly life influencing. At the core was a charismatic clinician-teacher. He immersed me in study of the nervous system, but more importantly into the deeply affecting human experience of intense and sympathetic engagement with a person seeking help for illness. I left medical school wanting to pursue a career in neuroscience guided by a prime role model of how people should be treated.

The encounters were a series of one-act dramas, real-life of course, set in the Neurology Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine in the 1960s. Most often the players were three, Ben Cooper MD, Professor of Neurology, our patient, and me, a third year medical student. A typical scene (one of many) was a new patient with a progressive tremor. I was the foil for the professor to play out his skill. The patient participated fully, an intensely interested partner watching somewhat dispassionately but with progressive fascination, the verbal dissection of his disease issue, mostly because it was done so artfully.

“What’s the diagnosis, Chief?” Ben Cooper queried me expectantly, his expression alive with enthusiasm that together we were confronting and sharing a new and profound revelation. Cooper, of course, knew the answer and also knew very well I probably did not. He also knew I would probably never forget it once he revealed his thought. I was sweating, not so much from fear of not knowing, but because I so badly wanted to please my mentor. He took such joy in sorting out the physical manifestations of a neurological disorder, putting them together with the patient’s complaints to locate the lesion in the nervous system and diagnose the disease.

He was so good at the process and so badly wanted me to share his joy, to partner in the quest. I was a willing but vastly less experienced participant in the drama. It was an emotional process, but I took away new knowledge and the patient a diagnosis and possible solution to his problem. In this real-life scene, our patient was suffering from a lesion in the cerebellum (part of the brain controlling coordination of movement) due to early multiple sclerosis. Cooper spent considerable time counseling the man, doing his best to comfort and encourage in a difficult situation. These experiences were among my best in medical school.

Ben Cooper’s patients loved him. No one treated them with more respect and caring than Ben Cooper.

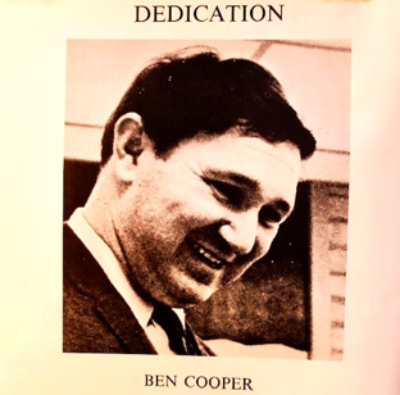

My classmates and I idolized Ben Cooper. “Chief” was how he always addressed us individually as students. The term was endearing and unique, nonjudgmental or prejudicial, made positive or negative (in our minds) mostly by how we performed in the clinical exercise. With his great shock of black hair, Ben Cooper always looked a bit impish. He was a big man who, but for his sport coat and tie, looked ready for a rugby match. His South African accent, refined by time spent at Queen Square Hospital in London, added to his air of authority. That he was married to a beautiful former model did nothing to hurt his image.

Ben Cooper was a master of theater. Done with craft honed by long experience, every clinical encounter was a scene, a touch of improv comedy except for the legitimate and apropos gravitas of the situation. The patient was part of the cast and invariably enjoyed the role. An occasional wry look from the professor in our direction or a wink made us feel part of some grand drama approaching its denouement. We felt privileged to be involved in a deep secret that was about to be revealed.

We stayed wary, however, because he could turn quickly to question us. Neurology was a complex subject and making accurate diagnoses by physical exam alone was a great art.

The language of British Neurology is colorful, often obscure but intended to be especially descriptive or accurate, for example Cranial Pachymeningitis, Gummatous Leptomeningitis, Tabes Dorsalis, all terms describing tertiary syphilis in the nervous system. The terms infer the location of the disease and partly describe the pathology, but fail to let on its origin is a sexually transmitted infection. Nevertheless, they seemed powerful and important descriptors as Cooper rolled them off, making the subject even more exotic. We loved it.

Ben Cooper’s patients loved him. They felt the depth of his caring. So did we. He had a collection of people who had suffered misfortune in the risk we all share as biological creatures, nature gone awry. They had various neurological disorders that made them essentially socially unacceptable, rapid violent movements, strange modes of locomotion, uncontrolled outbursts of sound, all of them intelligent beings afflicted with partial damage of their nervous systems. Cooper loved them and they him. They always readily participated in teaching exercises. No one treated them with more respect and caring than Ben Cooper.

With such a role model, me becoming a neurologist seemed an obvious choice, but I could not shake the desire to be a surgeon. Neurosurgery offered a compromise. I let Ben Cooper know. His response with a twinkle, “Chief, you’ve got to do what you want in life. If you want to go into the cut sciences, I can’t stop you.”

A couple of years after medical school, even after being accepted for neurosurgery training, I backslid even farther, opting for general surgery instead. Some rich experiences in the Indian Health Service influenced my decision. Moreover, I realized that I was most heavily drawn to the clinical work of neuroscience by my admiration and affection for Ben Cooper plus my intellectual fascination for the nervous system. However in my heart what I really liked to do day-to-day was pursue the “cut sciences” as a general surgeon.

I never had a chance to discuss my decision with the Professor. He died suddenly of a heart attack. A classmate reported his death expressing in a sad email the sorrow we all shared. I truly have no regrets about my career choice, but the nervous system still holds a fascination for me and I did my best always at the bedside to create joy in the encounter and the quality of human caring Ben Cooper taught me.